Discover how including video content in your job adverts will benefit you!

Find out with jobs.ac.uk why including video content in your job adverts can help you boost engagement and click-through rates.

Video content has become increasingly popular over the last 5 – 10 years and in 2024 it has become one of the most favoured online media formats. Video content is treated as more important to the market now than ever.

Studies have shown that browsers obtain 95% of a message when they view the content in video form, whereas the viewer only obtains 10% of text alone.

It is not unheard of for candidates to have multiple job options and browse from one advert to another.

How to make your job advert appealing:

Make your job advert stand out from competitors, using visual graphics and video footage to keep the viewer engaged and boost your employer brand.

Checklist for a more engaging and visually appealing job advert:

- Company Logo

- Images related to the job advert

- Video content

- Less Text

- Downloadable buttons for Job Descriptions and Further Particulars

82% of candidates now search for jobs on their mobile devices.

Video advertising is more popular than ever and has seen an increase in appearance in job adverts, helping jobseekers stay engaged and retain more information than a text alone job advert.

Increase visibility and engagement with video content in your job adverts

Video content helps increase visibility and keeps the jobseeker interested providing a high volume of engagement and connection. Including video content in your job adverts as a recruiter can help you, connect with candidates and showcase your brand and company.

Not only are videos great for engagement, but they work incredibly well on social media platforms like LinkedIn, Instagram and Facebook, which can help increase your brand awareness and widen your scope.

75% of browsers watch short-form video content on their mobile devices which is no surprise as viewers now want quick information. Over the years, the majority of recruiters have remained consistent, with the classic job title and plain text for their job adverts. However, studies show that 72% of candidates enjoy learning and retaining information through video form.

Not to mention online videos reach out to 92% of users on the internet worldwide!

Video advertisement can have a big impact on your job advert and if you are neglecting this medium, you are restricting your advert to capture the right candidates and showcase the full capability your company has to offer.

Overall including video footage in your job adverts can help boost ROI and drive new traffic and talent to your job adverts.

Enhanced adverts with jobs.ac.uk

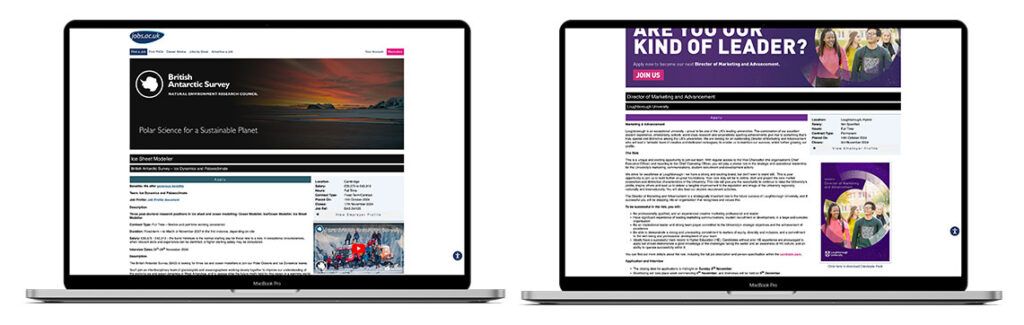

jobs.ac.uk designs their exclusive enhanced job adverts by including a logo, header image and a section on the right to include video content and additional job description buttons.

Recruiters have had great success with enhanced adverts, which help declutter the text and promote the recruiter’s brand in one advert, creating an unforgettable impression.

In the last academic year, jobs.ac.uk has had immense success with enhanced adverts, including video footage and the recruiter’s branding on enhanced adverts. proven to increase engagement and page views.

Make the change on your job adverts today and include your recruiter’s video with one of the UK’s leading job boards.

Share your comments and feedback